Can We Teach an Anti-Racist Architectural History?

Can We Teach an Anti-Racist Architectural History? A Toolkit for Future Workshops

This Toolkit is the result of two events, a Teacher-to-Teacher Workshop and a GAHTC Roundtable, both organized by Irene Cheng, Charles Davis II, Jia Yi Gu, Ana María León and Mabel O. Wilson. Workshop participants included Irene Cheng, Rebecca Choi, Charles L. Davis II, Gail Dubrow, Brian Goldstein, Mario Gooden, Jia Yi Gu, Marta Gutman, Dianne Harris, Samia Henni, Andrew Herscher, Ateya Khorakiwala, Ana María León, Sarah Lopez, Maura Lucking, Sean McPherson, Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, Mpho Matsipa, Kelema Lee Moses, Ijlal Muzzafar, Ana Ozaki, Rafico Ruiz, Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, Amber Wiley and Mabel O. Wilson. The following document and accompanying appendices were produced and compiled by Ana Ozaki and Jia Yi Gu.

Table of Contents

- What Is An Antiracist Architectural History?

Preliminary observations and answers from participants of the GAHTC Teacher-to-Teacher Workshop

- Introduction to Workshop Framework

Instructions for how to organize your own workshop with invited participants

- Suggested Workshop Sessions

A selection of possible workshop sessions and discussion topics

- Sample Session: Transforming Syllabi

An example of key lessons from one session focused on redesigning syllabi

- Sample Session: Objects, Texts, Case Studies

An example of key lessons from one session focused on objects, texts, and case studies

- Additional Sites of Intervention

Key takeaways from the GAHTC Teacher-to-Teacher Workshop “How To Teach an Anti-racist Architectural History”

- Selected Bibliography

What Is An Anti-Racist Architectural History?

Preliminary observations from the July 17th 2020 GAHTC Workshop

Antiracism in architectural history is not only focused on checking the boxes of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” by adding a few names and buildings (more diversity of gender and race, more geographic inclusion) to a roster of great works.

An antiracist architectural history reveals the systemic racism and white supremacy embedded in the discipline, and architecture’s complicity with empire and capital at large. Furthermore, it acknowledges that systemic racism intersects with other power structures of class, gender, sexuality, and body ability.

While it is attentive to revealing the structural racism embedded in the built environment, an antiracist architectural history also looks beyond it to histories and spaces of BIPOC resistance and liberation.

An antiracist architectural history centers BIPOC knowledge and language (as sources in our teaching; as ways of knowing/interpreting; and making space in the classroom for knowledge we and our students bring).

An antiracist architectural history is therefore also taught differently, with an awareness of students’ positions and experiential knowledge while also attentive to the problems of essentializing their identities (see: Lorde, hooks).

An antiracist architectural history is an activist history. It prompts students and institutions towards action and works towards the decolonization of the institution and of society, and, in the words of Saidiya Hartman, a “radical divestment in the project of whiteness and a redistribution of wealth and resources.” . It works towards our collective co-liberation, because until the most vulnerable among us are free, none of us are free.

Introduction to Workshop Framework

STEP BY STEP INSTRUCTIONS FOR ORGANIZING YOUR OWN WORKSHOP

Step 1. Organizing & Planning the Workshop

Identify a diverse mix of scholars, graduate students, organizers, and activists invested in teaching anti-racist histories of architecture and the built environment. The more diverse the better, given the different scales and topics this task entails, so consider different geographies, the nature of the student audience, the format (elective, survey, or studio courses), historiographical methods, among other criteria. An ideal group size would be around 20 people to give enough space and time for all voices to weigh into the general (but also smaller) discussions. Invite speakers that have worked in thoughtful, robust, critical, and creative ways within the scope of the topic. An array of approaches that includes those who teach in studios, seminars, and surveys could be beneficial in sparking productive engagements and ideas.

Step 2. Setting Expectations

After securing attendance and setting up the time for the workshop, make sure participants and speakers understand the expectations and goals involved. While they might all be invested in anti-racist pedagogies, limitations in time require a case studies format rather than content-encompassing. Sending the workshop’s schedule ahead of time, along with the intended set of presentations and discussion themes, might help temper expectations and help participants prepare for the discussion.

Step 3. On the Day of…

As a suggestion, you could follow the model presented in the sample Workshop Schedule. The overview:

Introduction and Community Agreements*

Session I: Transforming Courses and Syllabi (3 presentations at 10mins each)

Session II: Objects, Texts, Case Studies (3 presentations at 10mins each)

Closing Discussion & Template Brainstorm

Ideally the workshop time would be divided into shorter sessions. Each session could span an hour to one and a half hours, including speakers’ contributions and smaller breakout sessions of at least 30 min. The participants of the workshop can be organized into smaller breakout groups, in order to have many conversations at once and to allow as many people as possible to speak and contribute. You might want to rotate the note-taking responsibilities to ensure diversity of thinking and writing, as well as prevent fatigue. Recording the conversation is an important part of documenting and sharing the many thoughts and experiences. After the breakout sessions, bring all participants back to the main room to discuss each group’s main points or ideas that most resonated with the group members. A good practice is to assign different moderators for each session and breakout room discussion as without them exchanges can become unfocused.

*The Community Agreement is an important tool for establishing the workshop time as a respectful yet candid space of conversation.

Step 4. Take a Break.

Make sure to include small breaks between the sessions to allow reflection and to avoid fatigue.

Step 5. Collective Wrap Up.

For the final session, make sure there is enough time to discuss productive criticism and feedback of the workshop format, content, and discussions, as well as next steps moving forward. It is important to keep in mind that anti-racist pedagogy is a long-term commitment and while this workshop is a significant step in the process, it is not its final outcome. Make sure social, institutional, and digital infrastructures are put in place for the conversation to continue. The group might consider keeping a blog, a facebook group, or form a cross-institutional coalition, for example.

Workshop Best Practices

- Community guidelines - These could be set up in advance or during the first workshop session, as a practicing protocol for your courses.

- Collective note-taking - Before each session, moderators should remind the group to assign a different note-taker to avoid fatigue and allow an array of approaches.

- Strategies moving forward - It is important to keep in mind that for these strategies to work they need to go beyond the architectural history field and courses. You may want to discuss different ways (depending on how your institution is structured) to overcome specialized areas and encompass architectural departments and schools into the process. This should assure the longevity and sustainability of anti-racist pedagogy effort.

Suggested Workshop Sessions

- Workshop New Frameworks for Course Design: Collectively devise one guiding framework for course organization, syllabus design, or anti-racist pedagogy. You may choose as a group to focus either on the content (what is taught) or method (how) but we suggest you choose one or the other rather than tackling both, given the short time.

- Workshop Institutional Culture and Practices: How do we develop other approaches beyond the scope of history/theory teaching? How can history/theory teaching impact the work in studio, professional practice, and other courses? How can we stimulate thinking about how people teach and what they teach in studio?

- Workshop a Single Course: Get up close and personal with one course. Pick a race and space/architecture class and bring together a working group that actually sits with and workshops one syllabus with the instructor to discuss all components of the course, including readings, lectures, assignments, formats. Focusing on tension, conflicts, uncomfortable moments in the classroom, as well as moments of insight and discovery (both for the teacher and student). Invite students into this dialogue.

- Workshop a Single Module: Identify a specific module and workshop with colleagues a complete lecture, case study, reading list and discussion: Plantation House, Railway Infrastructure, Monuments in the South, World Expositions and Human Zoos

- Workshop a Reading Set: Identify a collection of readings that can be assigned over several lectures or weeks of coursework, and begin generating questions, discussion points, and lecture narratives collectively.

Sample Session: Transforming Courses & Syllabi

In this session, participants were asked to share the design of their survey course, addressing questions such as methods, categories, modules, and lecture continuity. Participants discussed unifying conventions such as chronology, geography, and historical actors, as well as ruptures to traditional survey formats. Each person presented for 5-10 minutes, followed by a group discussion. From the examples, workshop participants were asked to develop 4-6 guiding frameworks for course design. The following 5 guiding principles are the result of this exercise.

Guiding Principle #1: Critique the Canon

- Go beyond the critique of the canon by incorporating other disciplinary frameworks like Critical Race Theory or other methodologies like social history.

Guiding Principle #2: Situate Knowledge

- Shatter the perception that the survey is comprehensive, teach instead that knowledge is situated. We need to initiate a radical rethinking of course syllabi beyond logics of inclusion and diversity of examples.

Guiding Principle #3: Teach History Relationally

- Instead of teaching a periodized history of the canon that underwrites the Western architectural survey, thematically a single timeline, teach the history of building relationally and through complex temporalities. Prof. Charles Davis shares with students case studies in a “survey +” approach that cuts across time periods and geographies.

Guiding Principle #4: Empower students to be active agents in their own learning, not passive recipients of knowledge

- Develop classroom techniques that effectively teach students to engage critically, and also recognize themselves as participants within an inclusive and collective learning community. As bell hooks writes in Teaching to Transgress (1994), a "radical pedagogy must insist that everyone's presence is acknowledged.... To begin, the professor must genuinely value everyone's presence. There must be an ongoing recognition that everyone influences the classroom dynamic, that everyone contributes." This entails "deconstruction of the traditional notion that only the professor is responsible for classroom dynamics." It also requires professors to be vulnerable and to take risks themselves. Prof. Sarah Lopez, for example, “wants students to feel that they know what they know,” and that the classroom is a safe space to discuss their lived experiences, be vulnerable, test out new ideas, as well as make mistakes without being reprimanded.

Guiding Principle #5: Incorporate Anti-Racist Practices Across Curriculum

- Beware of silo-ing antiracist work in history and theory courses within the curriculum. Ensure that design studio, technology, and professional practice courses also incorporate anti-racism practices across the entire curriculum.

TEMPLATE FOR SESSION 1 DISCUSSION

SESSION 1

Come up with one guiding framework for course organization, syllabus design, or anti-racist pedagogy. You may choose as a group to focus either on the content (what is taught) or method (how) but we suggest you choose one or the other rather than tackling both, given the short time.

Each group please copy-paste your recommended framework or concept here.

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

Group 4

Group 5

Sample Session: Objects, Texts, Case Studies

In this session, participants were asked to share specific case studies, texts, or objects they have taught in their course in a presentation lasting 5-10 minutes each. From the pooled examples, workshop participants were asked to develop 4-6 guiding frameworks for developing robust case studies list. The following 6 guiding principles are the result of this exercise.

Guiding Principle #1: DEVELOP AN INTERDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

- Develop an interdisciplinary framework for your course that will introduce students to critical tools for studying race from outside of architecture that can be brought back to their discipline. The fields of postcolonial studies, critical race studies, literary studies, sociology, history, and political theory all offer important concepts and methodologies for analyzing race that architectural historians can draw on.

Guiding Principle #2: DEVELOP THE LONG HISTORY OF A BUILDING

- Diversify history by teaching students to see the long durée of a building, which often involves a diverse array of actors beyond the architect/designer, including builders, contractors, users, occupants, and critics. Provide students with the tools to trace the shifting users/occupants of a building to contextualize the ways it exceeds the intention of the architect/designer (ex. mapping of spatial use, oral histories, official and unofficial documents, etc.).

Guiding Principle #3: MOVE BETWEEN THE BUILDING AND THE BODY

- Replace an autonomous or isolated reading of a building for an engaged reading of the body in space; employ critical frameworks that enable students to interpret the tacit racial politics and rhetorics associated with a body in space; use architecture to illustrate the range of historical figures and characters that have acted upon a space.

Guiding Principle #4: REFRAME CANONICAL PERSPECTIVES

- Critique the limits and omissions of the canon by retelling standard historical themes and narratives through the eyes of previously marginalized historical actors. This enables you to acknowledge the different types of ‘knowledge’ that exist, from student perspectives to traditional peer-reviewed research.

Guiding Principle #5: PLURALIZE THE SOURCES OF HISTORICAL ARCHIVES

- Model for your students how one must pluralize traditional archives to recover the voices of those overlooked in architectural history (i.e. oral histories, ephemeral materials, journals, newspapers, ads, etc.).

Guiding Principle #6: LOCALIZE HISTORICAL LESSONS

- Racial history is not something that happens “elsewhere,” or in the distant past, but continues to shape nearly all the sites where we live, teach, and learn. Provide material case studies that a student can visit or research locally and that manifest common historical patterns. This approach trains students to apply what they learn immediately and continuously, and opens up possibilities for bridging research with activism.

TEMPLATE FOR SESSION 2 DISCUSSION

SESSION 2

Identify two artifacts (a reading, case study, assignment, etc.) that you would recommend including in a toolkit on teaching anti-racist architectural history.

Each group please copy-paste your recommended framework or concept here.

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

Group 4

Group 5

Sites & Scales of Intervention

Key takeaways from the GAHTC Teacher-to-Teacher Workshop “How To Teach an Anti-Racist Architectural History”

IN THE CLASSROOM

- The survey carries problematic implications. Is there the possibility of doing away with it altogether, while considering the importance of required courses that introduce students to the history of architecture? How do we retain the survey's ability to address students who might not sign up for a course on race and architecture?

- Challenge the automated inclusion of material, i.e. “just add things.”

- Antiracism is also a practice that extends beyond content. It includes reimagining the structures of teaching and a constant evaluation of the hierarchical relationships within the classroom, including teacher-to-student, student-to-student, and teacher-student-department.

- Instructors can establish the classroom as a liberatory space for dialogue, where mistakes are made and acknowledged. How can we as teachers model collective and engaged pedagogies that empower students rather than addressing them as initiates into these discourses?

IN THE INSTITUTION

- This year should be used to deeply examine curriculum in all courses, investigating how whiteness operates within each unit and discipline and then taking action to rewrite or rework each curriculum. Give time to this work.

- Rather than keep adding to the survey, how do you change the primary model itself? Challenge the very premise of a two-part survey course (the standard for most schools), which also means challenging extra-institutional requirements like NAAB and their implications.

- How do we extend antiracist pedagogy out of history/theory classes (where socio political questions are often sequestered) and into other areas of the architectural curriculum, especially studio?

- The “invisible labor” done by faculties of color is not typically rewarded with tenure and promotion. How do you value this? How do you support this?

- Recognize the work on anti-racism as intellectual work that engages the very episteme of western knowledge, and therefore should also be valued for its scholarly contribution and not only its institutional impact.

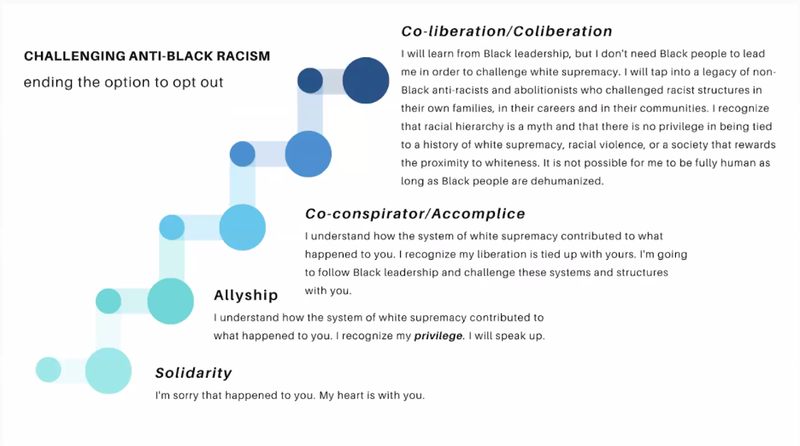

Credit: Tawana Petty, Shifting the Culture of Anti-racist Organizing

Selected Bibliography

An extensive number of bibliographies exist online as resources for course design. A select few include Space/Race Reading List and its counterpart Space/Race PDF Archive, Space/Gender, Asian American / Race / Architecture and Race, space an architecture: towards an open-access curriculum. Many of these lists are extensive. Below is an intentionally condensed list of key texts.

Institutional Subjects, Pedagogical Attitudes

The following selection of readings are initiating texts for those who are interested in designing new pedagogical frameworks for architectural history teaching. These texts offer entry points into teaching an antiracist architectural history that extend beyond content and curricular development. Instead, each of the following readings offer new perspectives and tools for how individuals, both educators and students alike, can cultivate, shape, and/or resist institutional frameworks and attitudes.

Ahmed, Sarah. “A Phenomenology of Whiteness,” Feminist Theory 8 (2007).

“Counterplanning from the Classroom: Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 76, no. 3 (September 1, 2017): 277–80. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2017.76.3.277.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (1991): 1241–99.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Lorde, Audre. "The Uses of Anger." Women's Studies Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1981): 7-10. Accessed August 7, 2020.

Moten, Fred and Stefano Harney. The Undercommons. New York: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press, 1967.

———. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Mbembe, Achille. Critique of Black Reason. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

paperson, Ia. A Third University Is Possible. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2017. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=2458655.

Robinson, Cedric J. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. London: Zed, 1983.

Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Silva, Denise Ferreira da. Toward a Global Idea of Race. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

Winters, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation -- An Argument.” The Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 257–338.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Architecture and Architectural History

There is currently a robust and growing body of work specific to architecture’s historical entanglements with race issues and ideologies. This selection of readings integrates interdisciplinary views in postcolonial, critical race, and feminist studies, and are in no way meant to be exhaustive, but rather seen as a collection of foundational, diverse and global methodologies in approaching the subject.

Akcan, Esra. Architecture in Translation: Germany, Turkey, and the Modern House. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Bristol, Katharine G. “The Pruitt-Igoe Myth.” Journal of Architectural Education 44, no. 3 (May 1, 1991): 163–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.1991.11102687.

Celik, Zeynep. “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism.” Assemblage, no. 17 (April 1992): 58.

Chang, Jiat-Hwee, and Anthony King. “Towards a Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Historical Fragments of Power‐knowledge, Built Environment and Climate in the British Colonial Territories.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 32 (November 14, 2011): 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9493.2011.00434.x.

Crinson, Mark. Empire Building: Orientalism and Victorian Architecture. Psychology Press, 1996.

Davis, Charles L. Building Character: The Racial Politics of Modern Architectural Style. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019.

Harris, Cheryl I. “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (1993): 1707-91. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341787.

Harris, Dianne Suzette. Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Lopez, Sarah Lynn. The Remittance Landscape: Spaces of Migration in Rural Mexico and Urban USA. 1 Edition. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Osayimwese, Itohan. Colonialism and Modern Architecture in Germany. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. First edition. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Wilson, Mabel. Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Wilson, Mabel, Charles L. Davis, and Irene Cheng, eds. Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present. Baltimore, Maryland: Project Muse, 2020. .