SAH GAHTC Teacher-to-Teacher Workshop: Backstage of the Global Histories Survey: Slow Looking, Translating, Listening, Activating

This Toolkit is the result of a Teacher-to-Teacher Workshop, convened by the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) and organized by Esra Akcan, Jia Yi Gu, and Rafico Ruiz with guidance from SAH First-Vice President, Patricia A. Morton.. The following document and accompanying appendices were produced and compiled by Ana Ozaki and Javairia Shahid.

This SAH GAHTC one-day workshop is conceptualized and moderated by Esra Akcan, Jia Yi Gu, and Rafico Ruiz with peer review feedback offered by Patricia A. Morton. It explores the backstage production of global architectural histories. While previous workshops have focused on the content and frontstage of presenting architectural histories in the classrooms, this workshop analyzes ways and processes to improve the global survey vis a vis its “backstage” or modes of production, engage with different pedagogical infrastructures, and expand long-term resources for teaching global architectural histories. Rather than comprehensive, it aims at forging and exploring a conversation regarding processes for more listening, a responsible scholarship that produces new and innovative knowledge, translating across languages and geographies, as well as ways of activating knowledge around multiple struggles around the globe. The following document and accompanying appendices were produced and compiled by Ana Ozaki and Javairia Shahid. The documentation and guiding principles of the workshop’s four sessions are not intended as a toolkit that can be deployed indiscriminately, but rather as a holistic sequence of phases that should be planned for and actively supported.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Workshop Framework

- An overview of the workshop’s pedagogical goals and processes

Session 1: Listening

- Global perspectives on teaching architectural history across geographies, from East to West

Session 2: Slow-Looking

- Ways to generate research-oriented and intensive global history courses

Session 3: Translating

- Samples of translation of texts as resources in building global history syllabi

Template for group discussion notes

- Documentation of group discussions and collective teaching frameworks

Group Reflections and Translating Guiding Principles- Breakout Session 1

- A selection of lessons learned and discussion topics from Session 1, 2, and 3

Session 4: Activating

- Examples of how to activate students toward global literacy

Group Reflections and Activating Guiding Principles- Breakout Session 2

- A selection of lessons learned and discussion topics from Session 4

Additional Documents Database

- Workshop Schedule

- Collective Notes - Breakout Session 1

- Collective Notes - Breakout Session 2

- Presentations

- Zoom chat

Introduction to Workshop Framework

This GAHTC one-day workshop is conceptualized and moderated by Esra Akcan, Jia Yi Gu, and Rafico Ruiz. It explores the backstage production of global architectural histories. While previous workshops have focused on the content and frontstage of presenting architectural histories in the classrooms, this workshop analyzes ways and processes to improve the global survey vis a vis its “backstage” or modes of production, engage with different pedagogical infrastructures, and expand long-term resources for teaching global architectural histories. Rather than comprehensive, it aims at forging and exploring a conversation regarding processes for more listening, a responsible scholarship that produces new and innovative knowledge, translating across languages and geographies, as well as ways of activating knowledge around multiple struggles around the globe. The following document and accompanying appendices were produced and compiled by Ana Ozaki and Javairia Shahid. The documentation and guiding principles of the workshop’s four sessions are not intended as a toolkit that can be deployed indiscriminately, but rather as a holistic sequence of phases that should be planned for and actively supported.

Session 1: Listening

This session centers on the question: How is architectural history taught across the globe? How do professional, institutional, and geographical frameworks influence our pedagogy?

Thomas Daniell (Japan), Kyoto University

While aware of the irony of a Westerner teaching Japanese architectural history in Japan, Daniell emphasized the possibilities allowed by an outside perspective in re-thinking hierarchies and categories. Daniell’s main goal has been to identify human commonalities rather than differences and alienism in Japanese architectural histories, especially considering that fifty percent of the student audience is non-Japanese and diverse in disciplines. This requires both technical and populous cultural understandings to produce contextual histories of the built environment. Daniell teaches two courses: “Buildings and Gardens (6th-19th centuries)” and “Post-war architecture,” and applies translations of lesser-known histories, materials, crafts, images, buildings, cultural practices, and theoretical texts to students, including the humanizing of actors through biographies, human backstories, gossip, among other media.

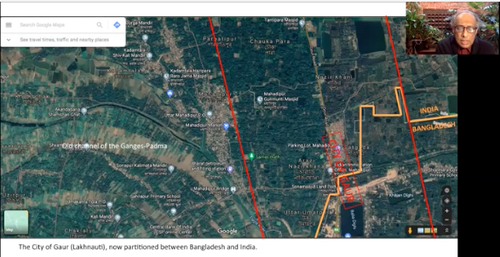

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf (Bangladesh)

[Image: Gaur: Now partitioned between Bangladesh and India]

Ashraf teaches architectural histories in an unconventional institute, outside of the cumbersome structure and rigor of a university. Bangladesh’s position within architectural history is tenuous: while Kahn’s buildings are included, histories of its region are not. Bangladesh, as a small nation in a regime of larger nations and histories suffers from an irreparable inequality, in which its existence is not a “self-evident certainty, but a wager, a risk.” With that in mind, Ashraf asks: How do we contextualize a work of art in the history of a small nation? How do we include smaller scales, such as the monumental architecture of Bengal, seen as a lower class or peripheral to the Mogul tradition and others from the Islamic centers? Histories of architecture should seek to explore nuanced differences between Islamic architecture, as well as within fractured nations and divided ideologies, such as the ones resulting from the bordering and partition of India in 1948. Architectural history is landscape and region’s history. In this context, the history of the Ganges river becoming the Padma in Bengal is crucial to historic and ancient capitals (Gaur, Bikrampur). As exemplified in Hawaiian history’s engagement with the Pacific histories and its other islands, Bengal’s historic understanding should address its connection to a Transoceanic network that connected China, India, Middle East, and East Africa.

Saba Sami (Iraq), Al Nahrain University

[Image: Approach: Tethering the historical to the local]

Sami addresses: how could teaching architectural history respond to local concerns while still having connections to the global transnational approach? The institutional framework of Al Nahrain University places architectural history as a precedent of architectural and studio practice. While the global context is taught throughout the programs’ curricula, local architectures are introduced intermittently. In this sense, Islamic architecture is seen as both global and local, and strengthened as the foundations of a local path, through the deep history of Mesopotamia, for example. While the history of other civilizations -- of four rivers, Aegean, and Latin America -- are included, the historical focus of the curriculum is thirty percent on Mesopotamian history, including its social, geological, climatic conditions, among other factors, as well as connections between simultaneous civilizations or styles. A descriptive methodology is used for their comparisons. Amongst the goals of the courses is to create in students architectural awareness, critical understanding of history and evidence, “a sense of the complex constitution of historical contexts,” as well as “raising awareness of the interconnectedness inherent in the historical course of architecture between the local and the global.” In this context, the course also brings out how positive precedents of local histories can inspire later architecture production, such as the Babylon Hotel in Baghdad by Edvard Ravnikar (1982), which engages with the Mesopotamia region typology (Assyria or Babylon’s Ziggurat).

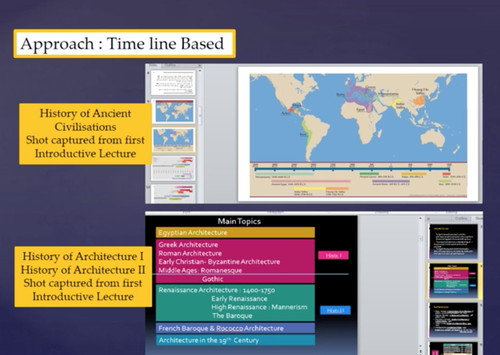

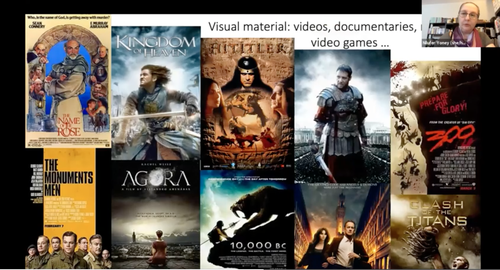

Nilufer Yoney (Turkey,) Mustafa Kemal University

[Image: Didactic Tools: movies, documentaries, and video games, scientific and archaeological open sources etc.]

Coming from an architectural and historical preservation background, Yoney teaches in a four-year architectural (BArch) program mainly centered on the studio. First year’s students are introduced to history, focusing on “design, culture, history, and technology,” their evolution, interconnections, intercultural relations, local to the global, thus, establishing an architectural literacy leading up to contemporary issues and narratives in the discipline. Courses include guest architects, who provide an overview of different skills, as well as assignments engaged in design skills (both written and visual). As a professor of preservation, Yoney’s lectures are organized through themes, for emphasizing global interconnectedness, and focus on technology, intercultural exchanges, and material use, amongst other factors. In the first year, students learn about first human settlements, social organizations, cultures, technologies, spatial needs, and uses. The second-year engages with the history of medieval settlements in Europe, the Near East, Anatolia and Asia, Renaissance, Baroque, Ottoman history, art, and architecture, as well as the rise of the individual artists and architects. In the third year, the course starts with the age of reason and the industrial revolution, then, progressing towards 19th century innovations, Ottoman Westernization, 20th century design theories, approaches, and architectures, and culminating in contemporary discussions in architecture. Global and local are presented at the same time and consistently. For the local context of Mustafa Kemal University, Antakya is the passage between the Near East and Anatolia. These histories are presented through a plethora of different visual materials: movies, documentaries, and video games, scientific and archaeological open sources, as well written fiction, popular history, and focused histories.

Adil Mustafa Ahmad (Sudan), Univ. of Khartoum

Ahmad brings to the table the contingent geopolitical context of Sudan and its implications for the teaching of architectural history. Architectural history, as in other contexts of the region, was formalized through colonial ventures such as the British Gordon Memorial College, established in 1902, at the onset of modern Western education in Sudan for colonial administrators and technicians. After independence, in 1956, it received full-fledged university status and the name of University of Khartoum. Branching out of the Engineering school, Khartoum’s architectural education was tailored along with the University of London’s approach and is taught in English. With that, the history of architecture follows a conventional stream, with Arab Muslim, Sudanese vernacular, and modern typologies stressed as precedents for studio, while other geographies and typologies remain general. Ahmad forefronts the struggles coming from independence and the country’s conflicting internal and external forces which directly reflect on life and education. Colonial structures and education, regarding the misinterpretation of religion and politics, remain in the Arab world of conservatory monarchies, military dictatorships, and theocratic states since free and secular education and research are seen as threats. Due to this context, architecture is associated with structural engineering rather than visual arts, and the Islam Arab thought is overpowering, presenting the architectures of Africa, Latin America, and Asia as a second tier of modern pioneers who blindly followed Western pioneers. Even in the Muslim faith, Sunni Muslim curricula do not include the Shia figurative art, for example, and follow religious thought blindly. Along with the mishappening of independence, which includes weak national governments, military dictatorships, religious fanaticism, 1990s’ sanctions, harmful foreign policies, censorship, the Islamization and Arabization of knowledge have put academic freedom and archaeological sites in danger. The precarity of other histories, exemplified in the permanent flooding of Sudanese Nubian archaeological sites, raises concern regarding the future of the field. Ahmad sees reform as the way out, through curing political systems, introducing democracy, confronting outdated thoughts, cultivating multiculturalism, secularization, and tolerance to other cultures, as well as students’ links to fine arts and humanities.

Huda Tayob (South Africa), Univ. of Cape Town

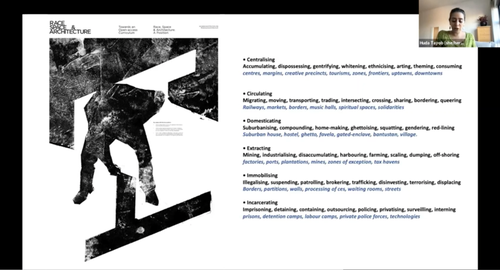

[Image: Race, Space & Architecture Didactic Schema]

Tayob presented both her course taught at the Graduate Architectural School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg and her collaborative open-access curriculum “Race, Space, and Architecture” (since 2018). This open-access curriculum centers on the entanglements and multiplicities of space-making and race-making while establishing them as foundational processes to modernity and modern architecture. More broadly, Tayob’s courses and pedagogical efforts question the boundaries of established methods, fields, and archives, and asks: what does it mean to speak of these from the margins? What does it mean to learn from outside of the discipline of architecture’s conventional boundaries? What kinds of lessons other types of creative texts or visual materials might make possible for architects? How do these lessons change our definitions of architecture?” The open-access curriculum is divided into seven frameworks: centralizing, circulating, domesticating, extracting, immobilizing, and incarcerating, across geographies and visual media, such as poetry, graphic novels, and others. Through these frameworks, the curriculum engages with race and architecture, locally and globally, as dynamic and transitive processes and movements. Moreover, it draws from Black radical thought (Mbembe, Fanon, Hartman, among others), regarding the links between the construction of race and racial capitalism to the transatlantic slave trade, as well as the possibilities and alternative approaches that this traditional offers. Tayob’s courses focus on balancing visuals and texts, intersectionality, interdisciplinarity, as well as collaborative publications and open-source media, such as collective Zines, Instagram pages, and websites, to engage with the issues in the economies of higher education.

Tom Avermaete (Switzerland), ETH Zurich

[Image: History of Labor: Liverpool and Mumbai]

Avermaete’s courses engage with the Janus-faced approach which implies both “situating cities and building in global geographies” and “the global in local buildings and cities.” For example, the course on the global history of urban design (part 2) taught to bachelors includes eleven lectures that address different economic, political, and biological processes, as well as cross histories based on thematic affinities. On the one hand, they focus on urban design projects with shared concerns, drivers, and outcomes, such as labor and housing of workers in the industries of Britain and India; cities and ideologies embedded in building for “healthy minds in healthy bodies” in Frankfurt and colonial Casablanca; new Capitals in Asia and Africa, such as Chandigarh, as well as “new institutions for old democracies” in Stockholm. On the other hand, situating the global within the local, the lecture “The Global Turn: Six Journeys on Architecture and the City (1945-1989)” touched upon global processes, including circulation of goods, knowledge, experts, materials, users/people, labor, among others, as well as resulting architectural typologies such as shopping malls in the US. The history of materials, such as glass and concrete, and labor, in the case of migrant workers in France’s bidonvilles, are also used as connectors across different geographies and urban processes.

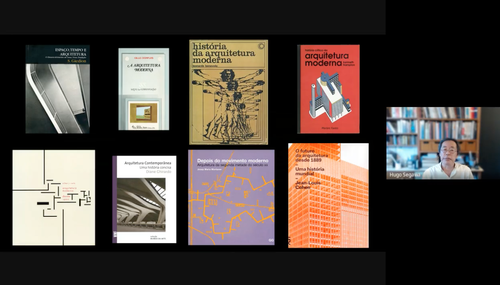

Hugo Segawa (Brazil), University of São Paulo

[Image: Recontextualizing Sources]

Segawa presents the textual tapestry that constitutes the foundations of global architectural history in the University of São Paulo’s architectural history courses. Favoring interactions with Brazil and Latin America at large, the context from the 1950s to the 1990s is presented through a multiplicity of translated texts from the Global North languages, including Benevolo, Gideon, Frampton, Curtis, Cohen, Montaner, to Brazilian Portuguese compose the Western canon. Focusing on the writing of architectural history, assignments include comparisons between different author’s approaches to similar subjects, to provoke a “don’t trust all you read” type of mentality. Another approach used by Segawa is lectures and roundtables with authors and students. Jean Louis Cohen was a guest speaker in 2020, followed by a round table with students and faculty, as well as with Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre, who talked about their second edition of Architecture of Regionalism in the Age of Globalization, and discussions about regionalism. These events also include non-textbook authors, such as Susana Torres, and her remarkable work on Women in Architecture, as well as more specific approaches to discourse and practice in Latin America, which broad’s scope would be impossible to cover through only lectures. More specific to Brazilian architecture, Segawa points out the plethora of local sources and written texts such as the ones by Yves Bruand (1981), Segawa (1998), Montezuma (2008), Williams (2010), Junqueira Bastos & Verde Zein (2010). However, this faculty expertise raises the question regarding the successes and shortcomings of such an education model in which professors and authors overlap.

Session 2: Slow-Looking

This session discusses ways of slow-looking for generating research-oriented and intensive global history courses. It centers on two inter-related questions: How can doctoral programs, research institutions, and other initiatives support scholarly research on previously unattended histories, fields, archives, architectural historical research? How can survey instructors be given resources to cultivate slow-looking in their pedagogy?

Steven Nelson, The Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art

[Image: Intersections: World Arts/ Local Lives, Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2016]

Addressing the dissonance between the zooming-in gesture implicit in slow-looking as pedagogy and the survey’s claim on the expansiveness of scope and span, Nelson positions the survey schematic by necessity, neither comprehensive nor all-encapsulating. Instead, interpreting looking in the broadest sense, he presents the survey as an invitation for students to recast specific objects in ever-expansive ways. In his seminars at UCLA, his students are asked to visit and write about campus buildings, focusing not just on the history or art historical value of these structures but also on the phenomenological or existential aspects of the building, their comparative interpretation in literature, film, photography and other media. In his practice, this methodology allows Nelson to bring seemingly disparate archives, materials, and sources together, across geographical, theoretical, and temporal expanses. Eschewing teleological interpretations, this mode of analysis encourages open-ended inquiry, framing what Nelson calls “throwing a lot of things up against a wall to see what's going to stick.” Equally, Nelson cautions against the perils of valorizing the richness of material while neglecting to acknowledge the inequitable nature of extractive knowledge production, calling for scholars to be cognizant of their situatedness and positionality—how we situate ourselves with respect to the material.

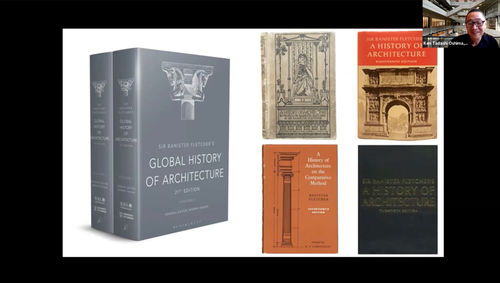

Ken Tadashi Oshima, University of Washington

[Image: Successive Iterations of Fletcher’s Tree of Architecture]

Across the breadth of the many different courses Oshima teaches, he engages with the nascent fluidity of the interpretive framework guiding the understanding of the built environment in architectural history. Situating the global and the local—alongside the oft attendant North-Souths, East-Wests-- as inherently unstable constructions, ever transformative and transforming when considered historically, Oshima calls for a collective, comparative perspective, that, for example, allows for looking and seeing the history of architecture in both Corbusier and Maki, and traces historiographic shifts in architectural history from the successive iterations of Fletcher’s Tree of Architecture.

Session 3: Translating

This session discusses the necessity of translation in facilitating the crafting of global architectural history and theory that prioritizes non-English language sources. Speakers shared methods and examples of translating for the positioning of primary texts as resources in building global history syllabi, and the challenges of translating texts on architecture.

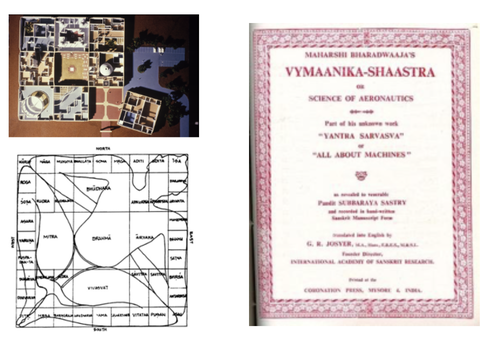

Farhan Karim, University of Kansas

[Image: Commonly used images in survey courses to discuss Vastu]

Karim’s survey course deploys architecture as the means of narrating the history of the world: by positioning architecture as a point of intervention, he invites students to appreciate and acknowledge the complex conditions against which historical texts and buildings were constructed. Employing translation as a pedagogical move, Karim presents the Vastu Shastra not just as a monolithic, didactic manual on the history of temple architecture in India, but as a document that points to the modes of knowledge production and epistemological frameworks occluded in such an interpretation and as a contested and evolving discourse. This approach informs the historic reading of the contemporary in Karim’s course. While the text subsumes and presents the world as in overarching theoretical discourse, concurrently it brings the world into this arched embeddedness and interdisciplinary in the present: as part of their coursework, students are encouraged to look through contemporary political contexts and contextualize them with the political ambitions and the contested nature of the past. Similarly, Karim draws attention to the attendant networks of patronage and authority that color the text, bringing to the fore questions of authorship, how the text was written, composed, compiled, and researched, how the information was collected, interpreted, compiled, and disseminated, in turn informing the ways we understand the making of history in the late 19th century. In presenting this decolonized translation of the text, Karim points to the pedagogical potential of re-translating the vast corpus of texts authored on the history of colonial India under British patronage.

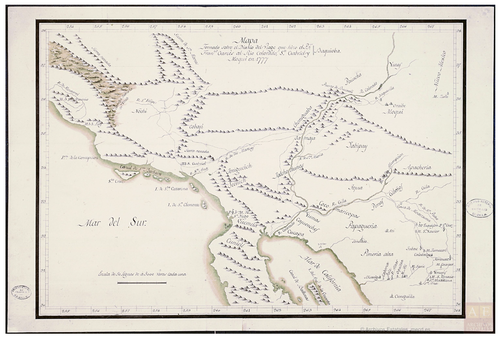

Manuel Shvartzberg Carrió, UC San Diego

[Image: Map based on the diaries of Francisco Garcés, 1777. Archivo de Indias, Seville, Spain]

What gets to be termed legitimate knowledge? This question informs Shvartzberg Carrió’s attempt to recover modes of inscription and erasure of Indigenous histories of unceded land. Taking the colonial map based on the diaries of Francisco Garcés, 1777 (Archivo de Indias, Sevilla, Spain) as an interpretive pedagogical tool rather than an authoritative historical document, Carrió mines the map for traces of the slow carving of colonial expansion that spans multiple empires-- first under the colonial process of exploration under the Spanish, then of US colonial expansion a century later, in what would become one of the roots of the transcontinental railroad through the Mojave with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Through close attention to the use of specific terms in translation, such as in the map’s references to Indigenous peoples as ‘nations,’ Shvartzberg Carrió gleans the shift in geopolitics as land and landscapes were transformed into colonial domains through processes of knowledge formation, such as cartography. As instrumental absences in the archives, oral histories provide a counter-point against evidentiary regimes deployed via instruments of colonization, including forms of written and visual inscription. Drawing from Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Shvartzberg Carrió notes how Indigenous knowledge is often mistranslated and reduced to ‘tradition’ rather than framed as legitimate knowledge. In turn, however, Indigenous knowledge practices – such as oral knowledge transmission – form a bulwark against colonization: knowledge is passed on from generation to generation in ceremonies of song where not everyone is allowed to listen. The difficulties of translation, in this sense, operate simultaneously as modes of insurgent secrecy, geopolitical diplomacy, and political technique.

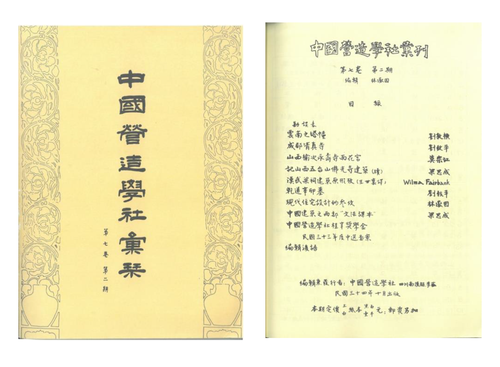

Eunice Seng, University of Hong Kong

[Image: Lin Huiyin. “References of Modern Housing Design.” Bulletin of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture (Oct. 1945): 1-3]

Examining Lin Huiyin’s role as a translator between architecture in China, where she worked, and Britain and America, where she was trained, Seng navigates her own position as interpreter, an insider outside -- opening a new perspective on Lin’s work in relation to her partnership with her husband Liang Sicheng, her interpretation of the vernacular and housing in post-war China, and how these insights inflect the history of Modern Chinese architecture. In 1945, Lin published an article on housing in the Bulletin of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture, vol. 7, no. 2 (Oct 1945). This article stands out as an exception to all the other essays in the 23 volumes of the entire publication because while it does focus on Chinese architecture and vernacular, it offers a survey of housing design in America and in Britain as the final proposal for the future direction for architecture in post-war China. This is unusual on two counts when read in conjunction with Lin’s previous work: first, prior to the publication of this essay, the primary lineage of housing in China was tethered to form the traditional Han dwelling architecture; secondly, this publication is also unusual because of Lin’s focus on the domestic—in the work she co-produced with her partner, China’s monumental and cultural architectural heritage served as points of reference for their pedagogical and design practice. In tracking the successive translations of key terms and ideas across translations that preceded Seng’s, Seng traces the shift from the import of tradition—exemplified in Han dwelling architecture-- to the notion of the commons, as Lin recasts notions of the individual, the collective and citizenry in her work. Similarly, Seng’s translation of Lin’s article leads her to reflect on Lin’s relationship with Liang, as she attempts to recuperate her work and authorship in relation to her partner.

Itohan Osayimwese, Brown University

[Image: A Maasai House]

Historians working on the history of architecture in Africa find themselves in a double bind: there is a dearth of evidentiary sources and archival material prior to the establishment of phonetic languages in Sub-Saharan Africa; the vast archive of material available by authors in other languages bears marks of its colonial patronage. Osayimwese leverages these texts by cannibalistically devouring them. In Afrikanische Bautypen, a series of forgotten German-language essays 1894-1898, Hermann Frobenius translated and synthesized five centuries of written sources in German and various other European languages on East-Central and coastal West Central Africa, to trace when the shift from round or curvilinear forms and floor plans to rectilinear forms occurred. Osayimwese acknowledges that historians such as herself are further alienated from Frobenius’s text by at least four degrees: by time, by culture, by space, and by language. Yet, unlike African scholars who are wary of adding another obscuring layer to what they call an already corrupted information or text, she argues for acknowledging this clear disconnect between reality and what is inscribed in these texts, and between signifier and signified in these European texts on Africa, free from the tyranny of a literal, inter-lingual translation. Reclaiming Herman’s mistranslations through re-writing rather than translation, Osayimwese transforms the text, not only correcting the inaccuracies but analyzing also the origin and proliferation of these inaccuracies. She proclaims translation a creative act, as a metaphor for intercultural encounter, as a linguistic practice involving intercultural mediation, shaped by asymmetrical power relations. Substituting words--mud for earth, or clay, or even Adobe—sutures together some formations while unraveling others, including the composition of the page--extensive footnotes and annotations on the translation occupy more space on the page than Frobenius’s actual text.

TEMPLATE FOR DISCUSSION

SESSION X

Come up with one guiding framework on potential methods for course organization, syllabus design, or pedagogy based on the principles from the workshop’s sessions (Listening, Slow-Looking, Translating, and Activating).

Each group please copy-paste your recommended framework or concept here.

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

Group 4

Group 5

Group Reflections and Translating Guiding Principles- Breakout Session 1

Drawing on the questions, comments, and notes of the breakout groups, below are a set of guiding principles that other instructors could build upon to incorporate translation in the classroom. These are principles that were generated through the collective effort of all workshop attendees, and that incorporate elements from the three preceding sessions (Listening, Slow Looking, and Translating). The narrative descriptions of the sessions above will ideally allow instructors who did not attend the workshop to understand the in-depth and diverse approaches required to lay the groundwork for meaningful ‘activation’ to occur around the essential question of global architectural history.

#1 Acknowledging scholars’ positionality

Participants focused discussions on the situating nature of session 1’s global mosaic, regarding teaching in different institutional, political contexts, and ranks, as well as ways to engage with the global across geographies. Issues regarding the positionality of teachers and students became especially evident through this lens, including the labor of junior scholars in relation to tenured ones.

#2 Disrupting the hegemony of Anglophone scholarship

On translation, discussions revolved around disciplinary boundaries and bridges, the prevalence of English and writing, as well as the perpetuating of Orientalist practices, which often see the non-West as the provider of empirical (rather than theoretical) knowledge. Participants especially highlighted the importance of soft skills, such as close-reading of images, texts, and media, and analyzing different modes of knowledge.

#3 Expanding citation practices

At the same time that participants recognized issues of untranslatability and rehabilitation of racist discourses, translation, and alternative media, including popular media, can offer different citation practices, historical evidence for decolonial thinking, ways of inclusion, and revisiting colonial prejudices and stereotypes.

#4 Engaging with collective modes of teaching, including students

In the context of the classroom, translation and global histories can be employed through collective modes of teaching, especially to make architectural history legible for design students and broader audiences. Such pedagogy should also address the power dynamics embedded in translation, engage with student’s knowledge, as well as explore global frameworks such as oceanic and environmental frameworks, rather than national. Moreover, it should help students to situate themselves within global and political contexts.

Session 4: Activating

This session yielded a set of recommendations (activations) on how instructors can cultivate activism in the classroom, through direct links to contemporary issues, and building geographical literacy.

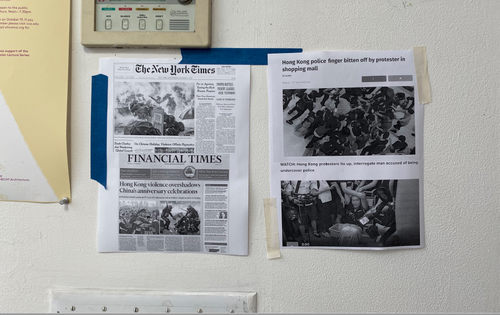

Irene Cheng, California College of Arts

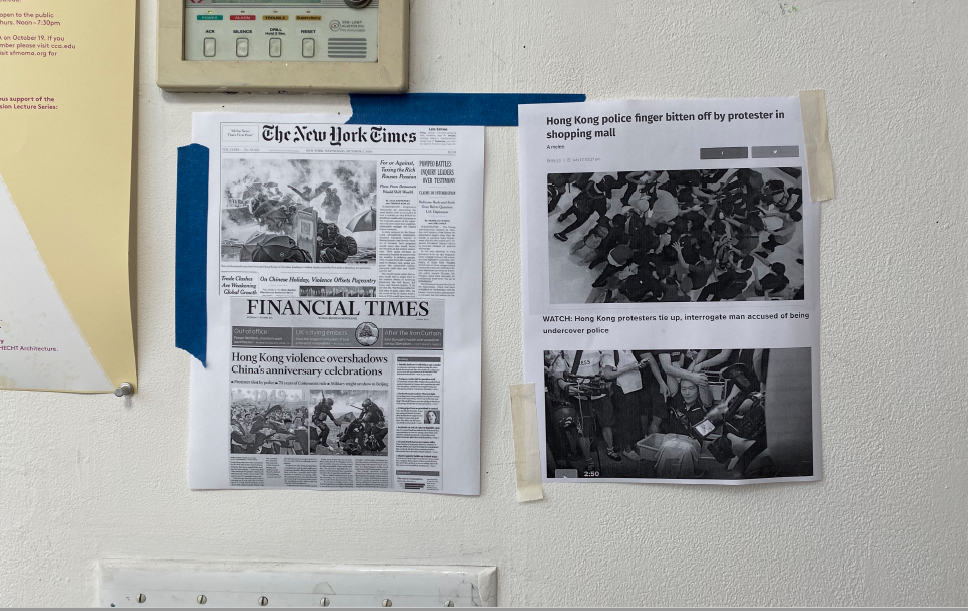

[Image: Teach-In: Make. Act. Resist]

Given San Francisco’s and the California College of Arts’s tradition of teach-ins -- a pedagogical tool created in the 1960s to bridge the worlds of academia and activism -- Cheng sees them as unique opportunities to address urgent current events and challenge hierarchical learning. Cheng presented three teach-ins events that she organized with other faculty and students addressing Black Lives Matter protests (2015), Hong Kong pro-democracy protests (2020), and Borders and Migration (2020). As an important precedent, the first aimed to create a safe space for students and faculty to discuss the BLM events, by suspending regular activities to encourage participation, as well as presenting talks and roundtables by experts, faculty, and students. Hong Kong’s protests teach-in took into account the significant number of students from Asia, as well as the disputing debates and point-views in its discussion, including within the global and local contexts. This event, with a similar format as the previous one, took on a larger scope of activism and Asia, for inclusion, with open discussions with an architectural historian from Hong Kong, art historian on China’s Tenement Square history, as well as an open forum, in-person and online, for people to speak spontaneously and without fear of retaliation. Finally, the Borders and Migration teach-in, which had been planned for the beginning of 2020 was adapted to a virtual format in the fall of the same year. It came up as a response to Trump’s nationalist rhetoric and included lectures, panel discussions, film screenings, talks by refugee activist groups, as well as a website for asynchronous participation. Overall, the successes rely on the fact that these topics were critical and urgent to students, which often spoke to their shared personal stories. They have also allowed synergies with the lectures and discussion of the architectural survey course. Although this type of space might not be available in other institutions outside of San Francisco’s tradition, they have the potential to open spaces for co-learning, for students to learn and practice soft skills regarding organizing, public speaking, and mentoring.

Daniel E. Coslett, University of Washington

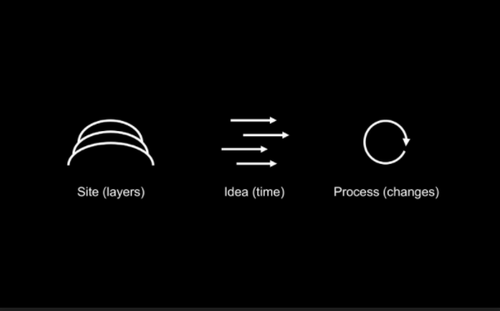

[Image: Concept: Site, Idea, Process]

Coslett emphasizes the importance of transhistorical relevance and architectural literacy in activating the classroom through deep investigations of site (physical and theoretical layers), idea (time), and process (building and changes). Current events are seen as starting points and opportunities to dive deeper into a building and related issues that may be applicable to others. For example, the recent closure of the Acropolium arts center (the colonial-era Saint Louis Cathedral) in Carthage by the Tunisian government in 2020 sparks conversation about its site, given the building’s complicated and multi-layered history. A lecture connecting the present event to the building’s past can engage with issues of religion, colonialism, globalization, heritage management, tourism, as well as Tunisia’s post-revolution democracy and identity. Moreover, its site, the ancient acropolis of Carthage, has been used as the foundation of colonialism and religious ideologies, and intellectual activities across colonial and postcolonial contexts. The US Capitol, which made headlines recently due to the violent insurrection in January 2021 and Trump’s executive order mandating the neoclassical style for federal government buildings, are loaded with complex symbols of the American democracy and architectural styles concerning empire, slavery, white supremacy, and notions of “civilization.” More than referencing ancient Athens, Coslett’s frameworks help us to discuss the many meanings of the building’s style and historical references, by considering other buildings deploying similar styles and ideas related to racism, fascism, colonialism, and white supremacy. In terms of process, Notre Dame de Paris is a useful example. Its 2019 fire and its coverage on the media regarding its reconstruction offer opportunities to engage with the ongoing process of (re)construction, including its initial conception, 19th-century changes by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, and the 20th-century replacement of architectural elements. Beyond discussion sessions, Coslett proposes specific activities to challenge students to find new stories about historic material today, including sketching exercises for new rooftops and towers of Notre Dame, appropriate styles and ideas for a new courthouse, as well as visiting accessible places, such as Western Washington University’s gym by Fred Bassetti, which references ancient Roman baths. Through such activities and close consideration of site, ideas, and processes, students are asked to consider links between historic and modern discourses and their relevance today.

Anooradha Siddiqi, Ana Ozaki, Javairia Shahid, Barnard

Modern Architecture in the World is a required course that serves a broad and interdisciplinary audience within Barnard College and Columbia University. This context often brings up asymmetries, between students, types of learning, among other aspects. With that in mind, the course situates the class within a global context and cultivates ways of co-teaching and learning, including students’ knowledge. Siddiqi approaches the digital classroom as an open space to foster dialogue and community, through lectures, discussions, asynchronous engagements, and assignments, which include discursive and spatial interventions with interlocutors and a political annotation/citation practice. As a living document, the syllabus and content respond to students' feedback to instill their intellectual independence historical inquiry tools, including getting in touch with local archives, including Avery, among other resources. The lectures' themes include colonialism, industrialization, war, revolution, urbanization, infrastructure, archives, partition, and migration, among others. They are made available before class and are anchored in a variety of objects, actors, multi-situated knowledge, ways of learning, and are presented as precedents of research methods. For example, the lecture on War and architecture raises issues regarding territory and land, embedded in Frederick Law Olmstead’s design and implementation of NYC's Central Park and the Chicago Exposition. Siddiqi contextualizes these projects within Olmstead’s storytelling ventures and trips, especially to Java, the Caribbean, and Panama, seeing the tropical flora as inspiration, as well as the US’s imperialism in the Panama Canal and beyond. In another lecture themed under infrastructure, the course circles back to this issue by focusing on the displacement of free African American communities such as Seneca Village, as a type of lost infrastructure, since as former property owners they lost the right to vote. Finally, the discussion sessions are led by both Siddiqi and the TA’s and focus on analyzing the boundaries and limitations of the discipline, as well as students’ interests and questions. It also aims at challenging power dynamics within the classroom to build solidarity and community, through teach-ins, such as the one led by present and previous generations of TAs, in the context of Columbia’s grad student strike in the Spring of 2021. Additionally, these efforts seek to acknowledge the TAs’ collective efforts to produce and disseminate architectural history knowledge.

Group Reflections and Activating Guiding Principles - Breakout Session 2

In response to the ideas and dialogues generated in the breakout rooms after the activating session, the following set of guiding principles meant for other instructors to build upon and create moments of “activation” in their own classroom settings.

#1 Linking the syllabus with current events

Discussion around the activating session focused on how to make architectural history’s material more relevant to students, especially regarding current issues and in challenging the status quo.

#2 Creating a livable and open syllabi

A livable syllabus and an openness to students’ different languages, backgrounds, personal barings, ways of knowing, and being are among the most critical strategies for the purpose of “activating” the classroom.

#3 Disrupting the hegemony of writing

Issues remain regarding evaluation methods and the hegemony of academic writing in the English language, for which different types of assignments, changes in medium, and ways of working can help.

#4 Safe spaces: the practice of academic freedom and global justice in the classroom

While these are potential practices, institutional and political barriers, as experiences not based in the US and Europe show, can offer career and life-threatening situations. Acknowledgment and engagement with academic freedom and justice are central. In this context open discussion, writing, annotation, redaction, and political citation practices can offer safe spaces of opposition since these are often less surveilled.

#5 Cultivating a global and inclusive community

Finally, activating can also take shape through the engagement with collaborators in order to de-center our positions and build solidarities. Interlocutors, collaborators, and students bring valuable expertise and experiences to the classroom. With this in mind, we should aim at fostering alternative spaces inside and outside academia and the university.